THE COMMUNITY OF Brinnon in Jefferson County was slower to develop than settlements farther north.

Although Elwell P. Brinnon had staked his claim at the mouth of the Duckabush River in the late 1850s — and he was not the first white settler in the area — by the 1880 territorial census, there were still only 58 people, white and Native American, living in the area.

The settlement along Hood Canal was not even named Brinnon until the post office was established there in 1891, and the government determined that the suggested name of Dosewallips was too difficult to spell.

Known by other names

From the 1850s through the 1880s, the area was also known as Quogaboos, or Ducaboos.

The location, 40 miles south of Port Townsend and the same distance north of Shelton, was described in a document in 1880: “Going eight miles south from the Big Quilcene we come to the Docewallops; two miles further to the Ducaboos, and four or five miles still further to HamaHama Creek — all of which flow into Hood’s Canal.

“The country along and between these streams is about all alike, being heavily timbered and rough quite down to the Canal, so that there is but little available farming land.

“On the Docewallops are now three families — Americans; on the Ducaboos one, and on the HamaHama, two.

“There are a few more good claims on these streams not taken. One or two logging camps, employing from five to 20 men are usually in operation here and the field for logging is extensive and favorable that it will for years yet be the leading industry.”

The lack of a land route to Brinnon, and the challenge of bridging the Duckabush and Dosewallips rivers, contributed to the isolation of the area.

Though settlers began petitioning the county commissioners for a road from Quilcene in 1870, it was only in 1894 that a primitive road began to be carved out on that route, and it wasn’t until the state highway along Hood Canal (now U.S. Highway 101) was completed that the area had an easily navigable land link to the rest of the state.

Oral history

In his oral history, Harold Gilson Brown remembered his ride from Quilcene to Brinnon in a horse-drawn wagon around 1913: “The old road was nothing but a winding, crooked, one-way trail over back of Mount Walker.

“It had been worked on by the county road crew a little, but if you met another team or happened to meet an old car, one or the other had to back up, to find a place to get by.

“As I remember it was very crooked, dangerous road along the rock cliff above the Quilcene River canyon, until you came to the downhill grade which went along Marple Creek on the other side towards Jackson’s Cove.”

The town was only truly accessible by water, with supplies and mail acquired from communities across the Canal.

But even arriving and departing from Brinnon on the water was difficult up through the early 1890s.

There were no docks for loading and unloading passengers and supplies. Those who wished to catch a boat had to stand on the shore and wave one down, then be rowed out to board it.

Similar experiences

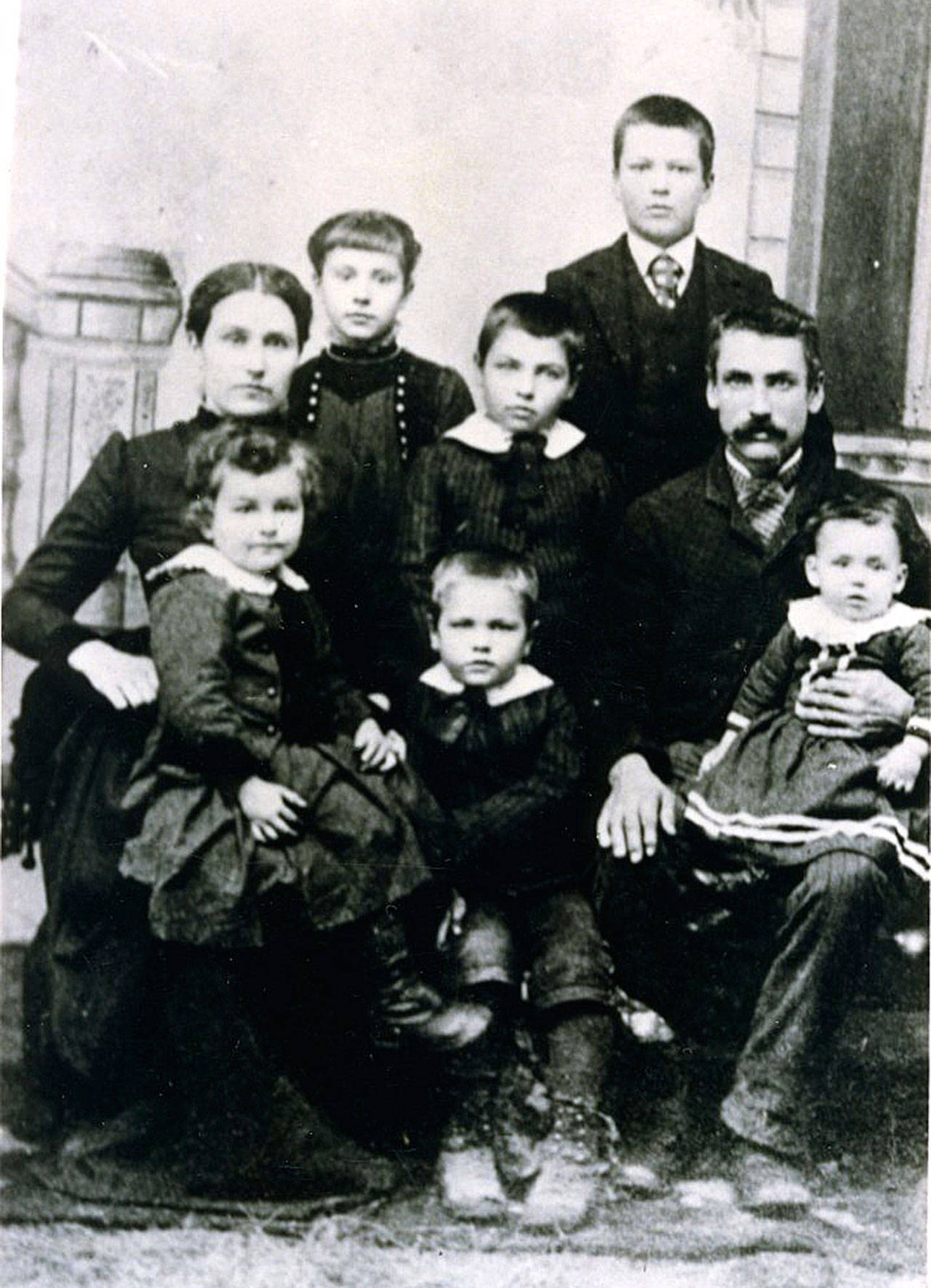

People arriving went through a similar experience to the one described by Allie Wilson, whose family arrived to meet the father, Mark Wilson, who had begun to establish a homestead upriver on the Dosewallips: “… we came to land at night. Dumped the cows in the water … to swim and then wade over the boulders to shore. Mother with six children [was] put in a row boat, then ashore at Ryerson’s logging camp.”

Later, Julius Macomber built one of the first stores near the waterfront, and a wharf at the south side of the tideflats that was used for passenger and freight services until highway services supplanted water shipping in the 1920s.

To reach homesteads and logging operations further up the rivers, there were only narrow paths through the timber.

Allie Wilson recalled, “The next day we start out for Mabons, 6½ miles up the Dosewallips from the beach. Henry drove the cows.

“Seemed like we walked all day … It got dark going up our hill.”

“Came to our cabin … hunters in there. Gave parents coffee and some hardtack,” Wilson continued.

“In the pitch dark, deep woods we headed for Mabons … We got off the trail.

“Pop hollered and here they came with torches of long sticks.

“So we moved in with the Mabons … 16 of us in one small cabin. Cooked on a fireplace.

“Everyone was happy … Lived there for two weeks until they got our one-room cabin ready. December, 1890.”

The rivers were crossed on foot on logjams, later replaced by foot logs. The foot logs were very hazardous, and several lives were lost by people falling from them.

Those driving horses and oxen for the logging operations had to ford the swift rivers. In the 1890s, settlers began to build plank bridges, but even those were hazardous when driving teams went across them.

Most homesteaders in the area were not only clearing land to farm but also worked in the logging industry.

The trips between the upriver homesteads and the logging camps were too long to travel every day, so the men spent the week in the camps, walking home on Saturday evenings carrying 60- to 80-pound packs of supplies and tools purchased with their earnings.

The women and children tended the homesteads, raising gardens, milking cows, raising chickens and keeping the forest from reclaiming the cleared farmland.

Many of the earliest homesteaders found life difficult enough that they left when they found more lucrative employment elsewhere, but there were always new people attracted by the rich bottom land, virgin timber and plentiful fish and game coming to replace those who had left.

Lillie Miller Christiansen had a wonderful memory and wrote many of her recollections of childhood along the Dosewallips.

She said that by the turn of the century, “there was a family every 160 acres up the rivers and along the beaches.”

Christiansen’s young widowed mother, Sarah, brought her three children west by train from Denver to Seattle, and from there on the steamer Delta to Brinnon, in the fall of 1892.

They joined Christiansen’s aunt, Mat Ryerson, at the Ryerson logging camp in Brinnon.

She and Christiansen helped in the kitchen where Ryerson was the cook, and the oldest child, Tom, worked at greasing the log skids with oil made from decomposed dogfish livers.

In August 1893, Christiansen’s mother married Eugene Wolcott, “a widower with a homestead and nothing. Mother had three children and nothing.

“We walked the trail four and a half miles deeper into the Promised Land, packing and carrying to the little two-room log house chinked with moss.

“The roof was of shakes. The floors were puncheon, smoothed down with an adz.”

Wolcott and Mark Wilson, who was their neighbor, were instrumental in establishing a school for the upriver children.

Wolcott donated the land. Wilson walked the 45 miles to Port Townsend to request a school from the county commissioners.

Christiansen wrote: “There was opposition but finally his plea was granted and a log schoolhouse was built.

“Dad made double seats of alternate narrow boards of maple and cedar. The desks were of a single cedar board … he planed the boards down, sandpapered and varnished them … beautiful work.

“He made the blackboards.

“Our first teacher was a young lady from Port Townsend [Lou Seitsinger]. At one time, 32 pupils were enrolled in the Upriver School.

“All grades were taught from first to 10th.

“The teacher had 40 classes a day; her pay $45 a month.

“One year we had an eight-month term. Usually we had six or seven.”

Both of these families were among those who established the Mount Constance Congregation Church and Sunday school.

Christiansen wrote: “We had no regular pastor and no regular church services.

“Sometimes Rev. Young used to come from [Seattle] across Hood Canal, walk upriver and hold services … Later Rev. Eells rowed his boat from Tahuya [the Skokomish Reservation] to Brinnon.”

Mark Wilson served as Sunday school superintendent.

Their isolated community drew the settlers of the Brinnon area close.

They were true neighbors to one another, sharing what they had with one another, joining together to celebrate holidays and marriages, and to mourn deaths.

More of their stories, as remembered by the young pioneers, will appear in the April 16 Back When column.

________

Linnea Patrick is a historian and retired Port Townsend Public Library director.

Her Jefferson County history column, Back When, appears on the third Sunday of each month, alternating with Alice Alexander’s Clallam County history column on the first Sunday of the month.

Patrick can be reached at lpatrick@olympus.net. Her next column will appear April 16.