SEQUIM — Scientists at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s Marine Sciences Laboratory are working to develop a new, low-cost process to draw carbon dioxide out of the air to grow algae that can be refined into alternative gasoline and jet fuel.

The beauty of fuel derived from algae is that it is “carbon-neutral,” meaning that the amount of carbon dioxide, or CO2, released when it is burned is equivalent to the amount the algae consumes during growth.

If it were cheap enough to be in mass production, algae-derived fuel could, scientists say, put the brakes on emission into the atmosphere of CO2, which accounted for 82 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States in 2012, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Many scientists link an increase in greenhouse gases to global warming.

It is important to find alternatives to fossil fuels and make them economically viable because “we are trying to solve the problem of global warming,” said Michael Huesemann, Marine Sciences Laboratory project lead.

“Therefore, the sooner we can find biofuels, or alternative fuels that are not emitting carbon,” the better it will be for the environment, he said.

Another benefit is that algae produces and releases oxygen as it grows.

“They make oxygen, so that is a good thing,” Huesemann said.

Algal oil, a byproduct of microscopic algae — a unicellular type of photosynthetic algae including up to 800,000 separate species worldwide — can be refined into gasoline and jet fuel.

But the current process of cultivating micro-algae on a mass scale is expensive because carbon dioxide absorbed during the incubation period is costly to mine from contemporary sources such as flue gases from power plants.

So scientists at the Sequim laboratory, using a $900,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office, are trying something new.

Over the next two years, they will cultivate micro-algae with CO2 derived from the atmosphere.

Success would mean that the cost would be reduced for cultivation on an industrial scale.

The amount of carbon dioxide in micro-algae growth ponds is regulated to provide the optimal amount needed by the algae during incubation, Huesemann said.

Too much carbon dioxide, and the water is not acidic enough for the algae to thrive; not enough, and the water becomes too acidic.

Without an external source of CO2 from which to pump into the growth ponds, the algae would be at the mercy of environmental factors just as in nature.

But CO2 sources generally are not located where industrial-scale micro-algae ponds can be constructed.

And even in places where industrial ponds can be built next to power plants, the cost of emitting carbon dioxide is prohibitively high.

But if a process of collecting CO2 directly from the atmosphere can be perfected, culturing micro-algae on an industrial scale would theoretically be possible.

“That is what ultimately the goal is — particularly in the American southwest or even Texas or Florida — that you would have many hundreds of thousands of acres . . . of these ponds producing biomass that is then converted via hydrothermal liquefaction to a green goo that can then be refined to gasoline, jet fuel or whatever,” Huesemann said.

Hydrothermal liquefaction is a process in which wet biomass such as algae, wood or manure is converted into crude-like oil by being heated in pressurized water to a temperature between 572 and 752 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the National Advanced Biofuels Consortium.

On average, it takes about a month of cultivation before the syrupy goo — the crude algal oil that can be refined into flammable liquid — can be derived from the algae.

“It is really nasty, but this is the stuff we want,” said Peter Chen, lab research associate.

Over the course of the project, the laboratory-led team will develop and demonstrate a new process called AlgaeAirFix, designed to overcome the energy intensity limitations associated with current air-carbon dioxide processes.

The novel process is estimated to produce up to 2,500 gallons of algal oil a year, meeting federal micro-algae biofuel program goals — which are based on algae grown from flue carbon dioxide — without the dependency on flue gas.

Research at the Marine Sciences Laboratory will concentrate the transfer of carbon dioxide from air into large-scale algal pond cultures using a combination of physical, chemical and biological processes.

The research facility is already conducting micro-algae growth studies in cooperation with Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, but with carbon dioxide not derived from the atmosphere.

Huesemann’s team of scientists also is researching types of algae for varying climates.

While some algae thrives at high temperatures, “there are some strains that work much better at room temperature” and “some strains from the Antarctic that die and wouldn’t grow in a warm environment,” Huesemann said.

Mapping how a particular strain will grow in a specific climate would allow industries around the globe to choose a strain that would thrive — whether the pond is in Germany or at the tip of South America, Huesemann said.

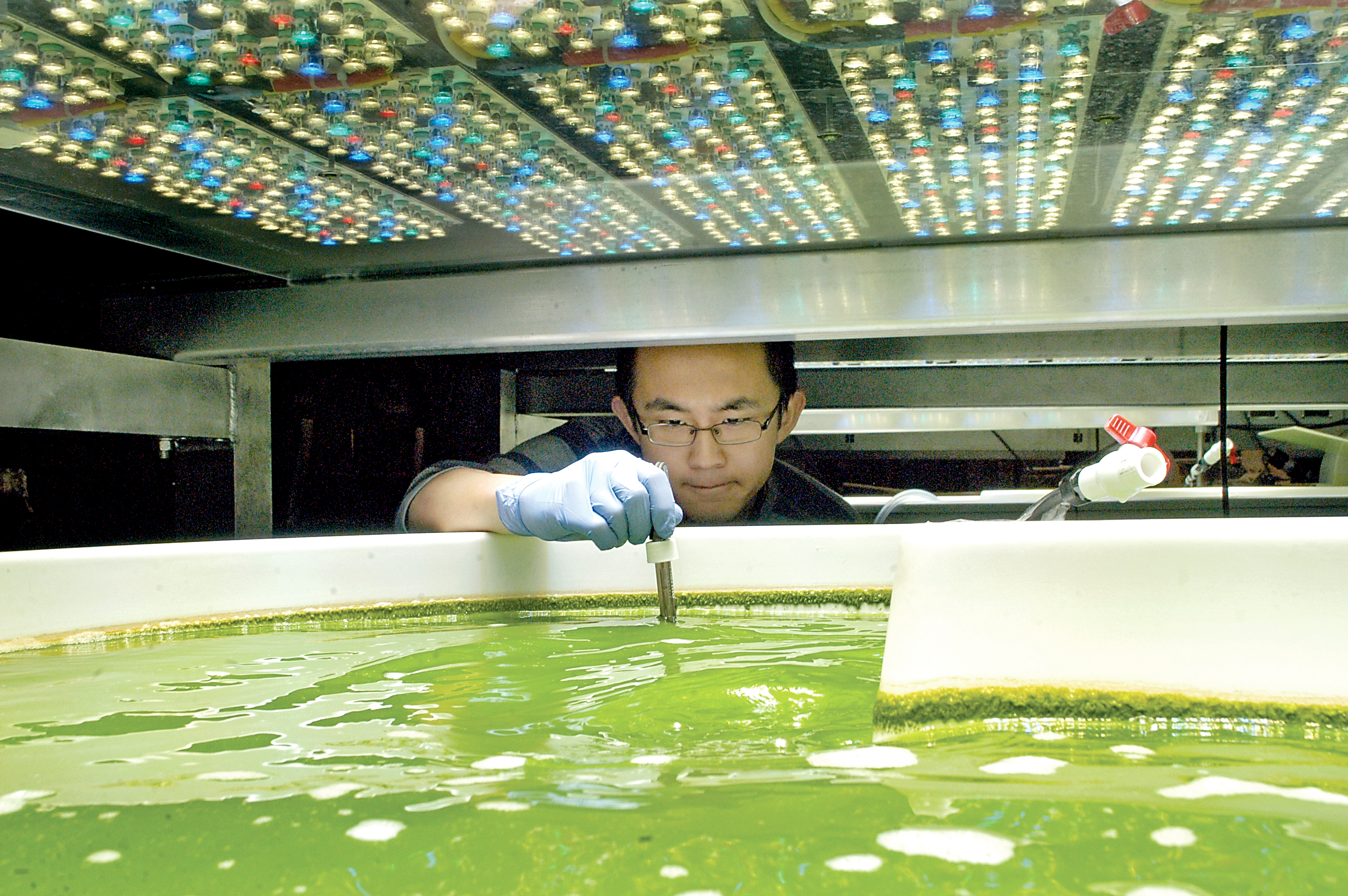

Scientists use three 200-gallon tubs to cultivate a variety of algae strains from around the world. A fourth tub is under construction.

The $100,000 fiberglass temperature-controlled tubs are equipped with thousands of LED lights able to simulate the full spectrum of sunlight and reproduce a variety of outdoor climate conditions.

The current batch being studied at the lab is the freshwater strain Chlorella sorokiniana. Some saltwater strains have been tested in the past, Huesemann said.

Scientists are careful to purge the algae from the water in the tubs before releasing it back into the bay, Chen noted.

They can’t “just dump it down the drain because we would introduce some non-native species” into Sequim Bay, he said.

“You have to pump it out, put some chemical flocculent to start binding the algae together, making it a nice green goop.

“It will separate from the liquid, and then you can flush the liquid,” he said.

________

Sequim-Dungeness Valley Editor Chris McDaniel can be reached at 360-681-2390, ext. 5052, or at cmcdaniel@peninsuladailynews.com.