By Molly Rosbach

Yakima Herald-Republic

YAKIMA (AP) — State Rep. Gina McCabe has an ambitious goal for Washington: to be the first state in the country with no backlog of untested rape kits.

But while the state task force established by the Legislature last year is making strides toward that goal, there are still years of work ahead to get through the estimated 6,000 untested kits, stakeholders say.

“I don’t think this was ever envisioned as something that would be all handled in a year,” said Capt. Jeff Schneider, Yakima Police Department chief of detectives. “This is going to take a long time to get actually under control.”

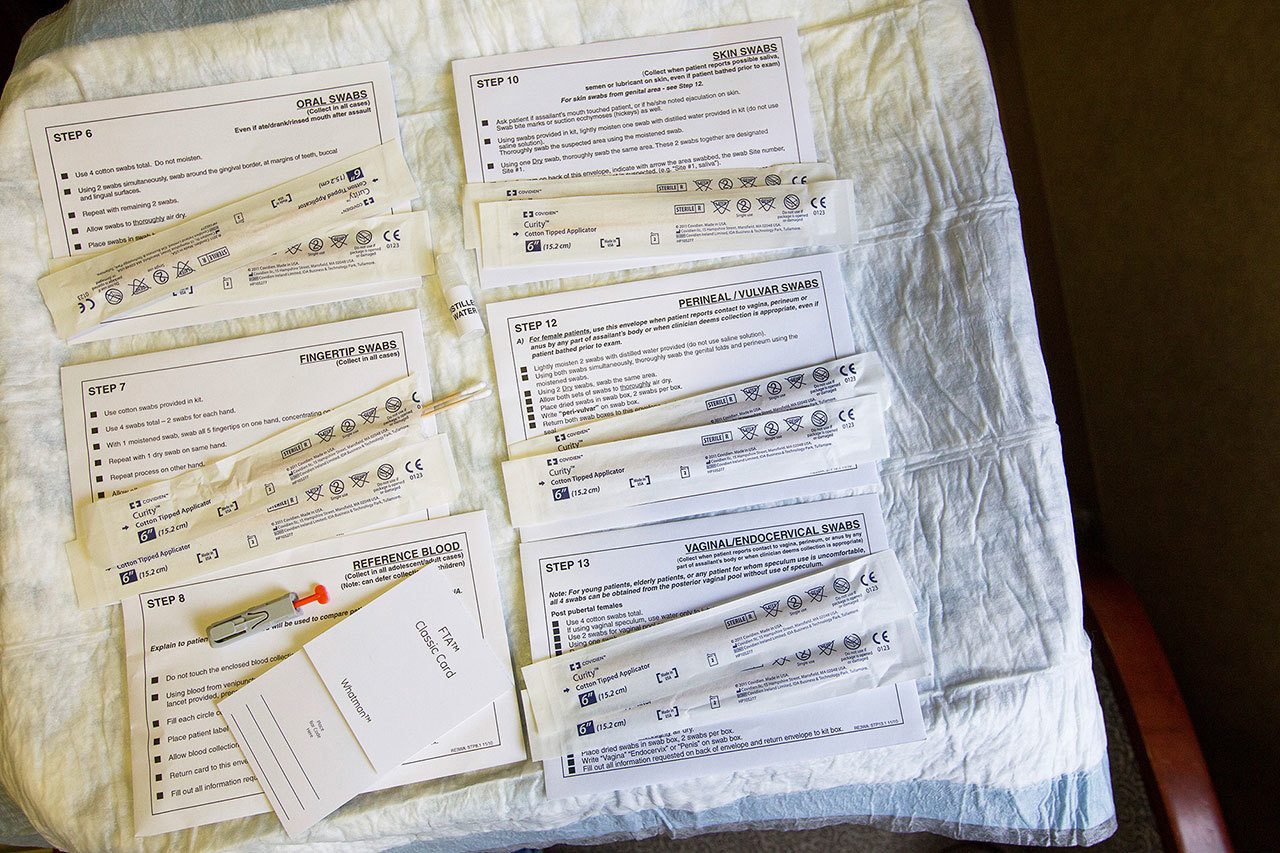

Washington’s approximately 6,000 kits — an estimate that came from a 2015 survey by the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs — are among some 400,000 untested rape kits nationwide, packets of swabs for DNA evidence taken in the aftermath of sexual assault in the hopes they will help bring perpetrators to justice.

Schneider didn’t have an exact figure of how many cases are backlogged in Yakima, but put it somewhere in the hundreds, reported the Yakima Herald-Republic.

The kits pile up at law enforcement agencies because the Washington State Patrol’s five DNA testing labs around the state don’t have the capacity to store all of them, and it takes a couple of weeks to process each one. Some date back at least a decade.

The backlog sends two messages, McCabe said. It makes victims question the point of going through an invasive medical procedure just to have the results languish in a box somewhere, and it tells perpetrators they will likely never be caught via DNA evidence.

Processing that DNA evidence is “exceptionally” important for court cases, Yakima County prosecutor Joe Brusic said. It also affects prosecutors’ relationship with the victim.

“It’s very difficult to tell a victim that there is this processing going on,” he said.

As one of the lead legislators on the task force, McCabe wants to address not only the backlogged evidence, but every piece of the process that interacts with rape victims, who often feel let down by the system.

“We have to go forward and do a better job as a state,” she said. “It’s just so important to tell the story, and make sure these victims feel whole again.”

In 2015, the first law addressing the rape kit backlog established a state task force of legislators, victim advocates and other stakeholders and required law enforcement agencies to submit a request to the state labs within 30 days of receiving new rape kits, if the victim consents. The kits stay in the police station until the lab has space to receive them.

While the law did not include a specific requirement to clear out the backlog, it directed the task force to develop best practices around processing the previously unsubmitted kits.

It also came with funding to hire and train new forensic scientists for the State Patrol’s labs to increase their evidence-processing capacity. Six of the seven spots have been filled.

Total, the state labs employ 43 DNA casework positions, but only 29 full-time equivalent scientists are qualified to perform DNA casework. Five are still in training, and seven positions remain vacant.

Of the new hires, only one had any experience coming in, and the rest require 18 months to two years of training, even though they come with bachelor’s or master’s degrees, said Jean Johnston, the CODIS laboratory manager. (The state’s CODIS lab is tasked with comparing DNA profiles taken from the kits against the FBI database.)

“It’ll be another year or more before these new scientists are able to produce casework,” Johnston said, adding that in that time, the labs might also lose some of their experienced DNA scientists. “It’s a constant struggle to have enough staffing to be able to process the samples.”

It takes 10 to 12 hours of work to process each kit, but as certain tests take time, those hours are spread over a week or two. Forensic scientists also are called out of the lab several times a year to testify about the evidence in court cases, which might take an hour or several days.

To address the backlog, State Patrol labs are contracting with a private lab that will focus solely on previously untested kits, while the state labs continue processing new kits that come in — along with evidence from all the other homicides, assaults and robberies that flood the system each day.

It was only in the past few weeks that the state got results for the first 200 or so rape kits processed by the private lab. A report will include how many CODIS hits came through, McCabe said.

Earlier this year, the Legislature passed a bill to establish a tracking system for rape kits, so they can’t fall through the cracks or wind up forgotten in a police station closet.

The law directs the State Patrol to develop the system, which will eventually allow victims of sexual assault to log onto a secure website and see exactly where their individual kit is at any point in time.

Another bill this year called for a study of how to increase the availability of nurses specifically trained to conduct sexual assault examinations (Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner, or SANE nurse), or how to better utilize existing nurse resources across the state.

Properly trained nurses are critical not just to prevent the re-traumatization of victims in the exam room, but also to testify in court about the evidence they gathered and witnessed during the exam.

At Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital, about five nurses have gone through the full SANE training, but every nurse in the emergency department receives a four-hour training from case manager Dee Demel, so they are all prepared to do a sexual assault exam.

Beyond the medical technique needed to collect meaningful evidence, the course addresses the emotional component of the exam, both for the victim and for the female nurses, for whom rape is a very real fear.

Exams take two to four hours, and generally include an interview with police. The hospital also calls local victim advocates if the victim consents. Victims are not billed for the exam.

Demel said what she’d most like to see is a separate facility to treat rape victims in a more comforting environment, away from the noise and harsh light of the emergency department.

Community advocates play a big role in guiding and encouraging victims through the legal system, sometimes following cases for years.

“They help the victim stay in the system,” McCabe said. “If you have someone who’s holding your hand, giving you coffee or a warm blanket, you’re more willing to stay in the system,” working with police and prosecutors.

Advocates help connect victims with services such as counseling, inform them of other resources they can pursue, and help them keep track of all the meetings and contacts that accompany a criminal court case.

Statewide, the task force has found that advocates are underused, though Yakima Valley advocates say they have strong working relationships with law enforcement and hospitals, and are able to respond 24/7.

Ensuring that police and nurses always call for an advocate depends on “continuous outreach, not just a one-time thing,” said executive director Leticia Garcia from Lower Valley Crisis and Support Services. “It’s not a perfect system, but we’re here to provide that support and to collaborate.”

At the state level, upcoming priorities include securing more money for the police and prosecutors investigating cold cases, and potentially eliminating the statute of limitations for prosecuting rape cases, McCabe said.

“It seems like the more we do, the more there is to do,” she said. “But it’s important work, and I think we’re going to get through all of it.”